Why Does NJ Transit Keep Canceling Trains?

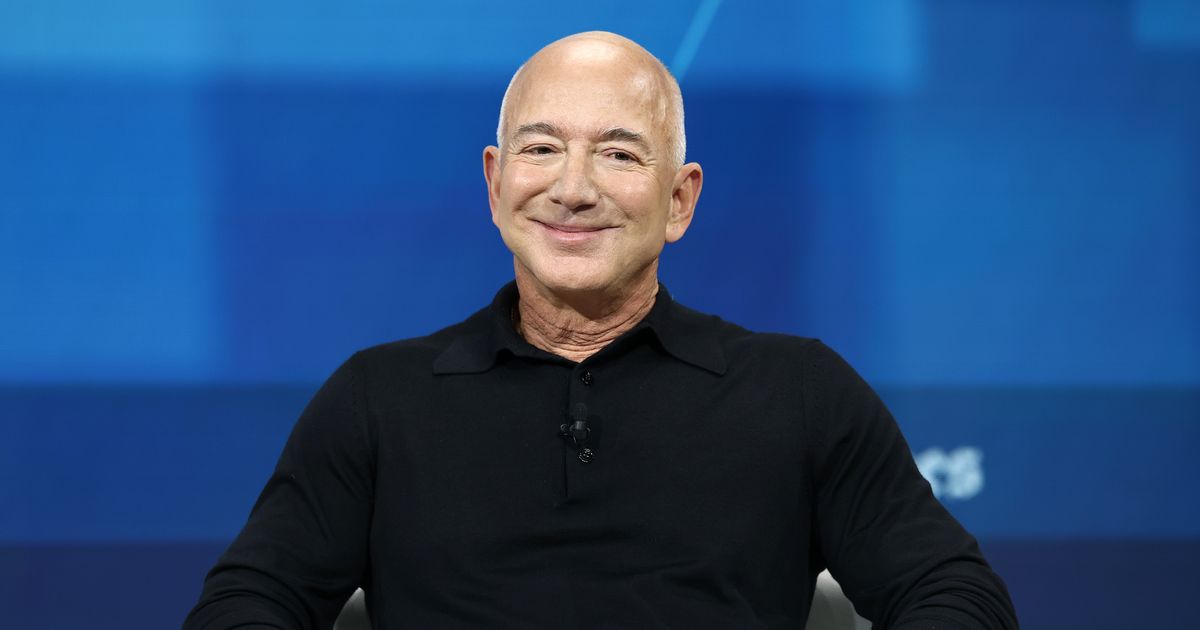

Photo: Yuki Iwamura/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Stuck in the dark, hundreds of people were crammed aboard the 7:20 p.m. New Jersey Transit train to Trenton on July 31, as it sat in the tunnel beneath the Hudson River. They just wanted to get back to their homes in the suburbs, and the railroad that they depended on failed them in epic fashion, leaving them stuck under the river for two full hours. In an extra indignity, they’d bought their tickets just after a 15 percent fare increase on July 1, meant to patch NJ Transit’s threadbare post-pandemic finances. NJ Transit blamed Amtrak because its ancient power system had failed. Amtrak blamed NJ Transit because its 50-year-old train wouldn’t start after the electricity came back on. Afterward, the commuter railroad nonetheless defended itself. An unidentified spokesman wrote the following e-mail to a reporter, recently obtained under New Jersey’s open-records law: “NJ TRANSIT operates nearly 700 trains a day, and our latest on-time performance data from June indicates our trains were on-time 83% of the time, adjusted to 92.3% when you account for issues related to Amtrak infrastructure. This is far from disastrous.” They might as well have decided to challenge the existence of gravity.

The misery has spilled out across the system. One commuter recounted a miserable week in June that hit its nadir on Thursday the 20th, when his train home to South Orange was canceled from Penn Station, forcing him to try to get home from Hoboken, whereupon that train ended up getting canceled too. He got home after 8:45 p.m. “It was kind of a disaster,” he recounted. Another, also a white-collar professional, told me that he now allows an extra hour for every morning commute, just in case. “You have to block off this buffer time because you have no idea what’s going to happen that day.” He moved to New Jersey from Brooklyn after the pandemic. “Every single morning into the city, we just stop in the swamp with no cell service and it’s like ‘Well, how long is this going to be?” he said. “There are points in time where it’s had me reconsidering my job and reconsidering that we bought a house.”

Two crises are unfolding simultaneously at NJ Transit. The first is well documented and mostly outside NJT’s control: Despite years of promises and assurances, Amtrak has failed to maintain or modernize the power grid along the Northeast Corridor, which also serves as the trunk route for many NJT railroad services. The second is that NJ Transit, starved by both Republican and Democratic administrations in Trenton, can no longer meet one of its most basic responsibilities: Keep people moving. The agency canceled nearly 3,400 trains between January and August, or about a hundred a week. That’s seven times as many cancellations as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North, which nixed 530 scheduled runs combined. It has been getting worse, not better: Over the first eight months of 2024, NJ Transit’s commuter system logged 1,200 more cancellations than in 2023. NJ Transit loves to point the finger at Amtrak, which operates a lot of its tracks, yet the analysis of agency records shows that NJ Transit acknowledges the bulk of the cancellations this year have not been Amtrak’s fault. Even if you subtract those that NJ Transit can pin on Amtrak, the number still stands at more than 2,300, up year-over-year by 800.

Another way to gauge reliability is the average number of miles trains run between breakdowns. The silver-and-red train sets the MTA uses on the New Haven Line, known as the M8s, are tanks. They go 800,000-plus miles between failures — three trips to the moon. New Jersey Transit trains are breaking down 16 times more often, averaging 49,378 miles. The stats are bad enough that New Jersey Transit had to redraw the chart on its website where it publishes performance statistics so the line literally didn’t fall off the page.

NJ Transit management cites the advanced age of its fleet, which is an explanation that’s tidy and easy to grasp — and only somewhat fits the facts. (The agency did not comment for this story by press time.*) The Bergen Record’s transportation reporter, Colleen Wilson, recently spotted a filing with the NJ Transit board of directors, dating back to 2022, that showed the reliability of the railroad’s newer passenger cars had also hit the skids. When she asked for updated stats, the railroad refused to provide them (and similarly refused to provide the data when I asked again). Data that the agency files with the U.S. Department of Transportation annually helps fill in the gaps: It does far less maintenance on its commuter railroad trains than the MTA does. (In 2023, Metro-North’s trains operated for a combined 4.9 million hours, virtually the same as NJ Transit’s 4.7 million hours. But Metro-North’s workforce combined to do 3.2 million hours worth of maintenance on its fleet, compared to just 2.6 million at NJ Transit. NJT also did less maintenance time in 2023 than it had the previous year.) “We’ve allowed the system to get brittle bones,” said Zoe Baldwin, the top expert on NJ Transit at the Regional Plan Association. “It affects more than that day’s commute. Not everyone has the luxury of being an hour late because your train was canceled, or an hour late to pick up your kid. This has very far-reaching implications. ” New York pays more for its trains, in taxes and fares, and sees the difference in service.

Phil Murphy won office in 2017 by promising to turn the page on the governorship of Chris Christie, whom he accused of turning NJ Transit into a “national disgrace.” In his 2019 budget speech, he declared that “if it kills me, we’ll rebuild NJ Transit.” In a press conference at Secaucus Junction, he told reporters, “Enough is enough. It’s time not just to clean the house but to knock it down and rebuild it.” Yet more cracks in the façade quickly appeared. He wouldn’t commit to a substantial increase in NJ Transit’s budget for running service or maintenance. Nor would he commit to major investments in trains and stations. Murphy’s single big idea was freezing fares, good for public relations but no more effective a repair strategy than his predecessor’s financial strangulation of the system. Christie, though, shares the blame not only with Murphy but with their predecessors: He was the latest of several governors uninterested in funding transit. In 2004, Trenton allocated $618 million for major projects, modernization and improvements at NJ Transit, or approximately $1 billion in today’s money. In 2024, Murphy and lawmakers allocated just $760 million for the fifth year in a row — a shortchange that adds up to $2.4 billion per decade. That doesn’t sound like rebuilding “if it kills me.”

Even when everything works, the lack of funding slows down commutes. The MTA, for example, uses a pricier station design than NJT, one that elevates the platforms used for boarding and disembarking four feet above the tracks. Passengers can step on and off the trains quickly, without stairs, cutting the amount of time they spend in stations and speeding commutes. New Jersey still has dozens of stations with platforms that are only a few inches above the ground. The design is cheaper to build, and it slows down every single stop. It also has a ripple effect: NJ Transit’s train cars need two sets of doors at each end — one with stairs and one without — to deal with variable platform heights, and that means the doors are narrower, creating more bottlenecks. (Wheelchair users also run into real problems there.) It boils down to this: Metro-North and Long Island Rail Road trains typically need just 30 to 40 seconds at each stop while NJ Transit’s need a minute or more. The MTA has also invested a lot of money in fitting its trains with the type of electric propulsion system typically found on subways, dramatically improving their acceleration and deceleration. That cuts another 30 to 40 seconds off each stop. NJ Transit’s trains are typically hauled by locomotives, which are slower.

These little second-by-second increments sound dinky, but they add up fast. Shave off a minute-plus per stop from a commute in each direction, on a route with 12 stops, and you get 12 minutes back. Over the extent of ten runs on that track, you’ve cut two hours. You can run a bunch more trains in that extra time. You can see the difference in the timetables: It takes a Metro-North train 58 minutes to go between Stamford and Grand Central, making a half-dozen stops along the way on a track full of curves that is capped at 75 mph through Connecticut. A NJ Transit train going about the same distance to New Brunswick, mostly on a straight run that ought to be able to handle almost double the speed, takes the same amount of time, because those trains are so much pokier.

The importance of throughput — that type of keep-everything-moving detail — has become the focus of a research project that I’m working on for the Marron Institute at NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering. Early projections from the NYU-Marron research show that it would cost approximately $10.5 billion to electrify and upgrade (including building those high-platform stations) every NJ Transit line serving Penn Station or Hoboken to the MTA’s standard. It would take time, probably ten to 15 years, to fully install the program. But, by the time it was done, a commuter coming into Manhattan from Trenton on the 7:46 a.m. train would see their commute shortened from 93 minutes to 72 in each direction — putting nearly three-quarters of an hour back in that person’s day. Each train carries more than 1,000 people. That is a lot of family dinners going unmissed, of school plays and Little League games unskipped.

I’ll note here that the state that won’t pay to keep its trains in working order, never mind make the investments needed to deliver speedy and reliable service, has instead found a nearly identical amount of money for something else. It wants to spend $10.7 billion to expand the leg of the New Jersey Turnpike that runs from Newark Airport to Jersey City, including building a second bridge over Newark Bay. The environmental review for the bridge alone is a case study in its futility. It reveals that this expansion will raise the highway’s eastbound capacity from 4,500 cars per hour to 6,000. That’s roughly one train’s worth of people, for the cost of modernizing all of NJ Transit’s rail service.

How did an administration that came to office promising to rebuild NJ Transit starve it with a fare freeze, then reverse and raise those fares anyway? How did that administration punt on finding new funding for NJ Transit until it was in mid-collapse, then come up with a rescue plan that flows through the general fund, where it can be easily diverted from NJ Transit when nobody’s looking? Murphy, this summer, provided an answer. He was asked during a press conference with Amtrak executives on June 27 in Newark when he last took the train. Murphy touted his “largely very good experience” before eventually admitting he doesn’t ride it much. “It’s been several months,” Murphy said. “I’ve got to get back on it.”

*Update, October 28, 4:10 p.m.: Shortly after publication, New Jersey Transit responded to say it “strongly disagrees with the premise of your questions, along with your misuse of the data,” claiming that the comparisons with other railroads are inexact. The railroad avers that when events not under its control are excluded, its performance statistics significantly improve, and that NJT’s newer trains, purchased since 2018, are dramatically more reliable than the older cars in the fleet. It also disputes the assertion that fewer maintenance hours correspond to lower reliability.

Source link