Three-Person Mitochondrial IVF Leads to Eight Healthy Births

Eight Healthy Children Born Using Three-Person IVF Technique

Long-awaited results of a three-person IVF technique suggest that mitochondrial donation can prevent babies from inheriting diseases caused by mutant mitochondria

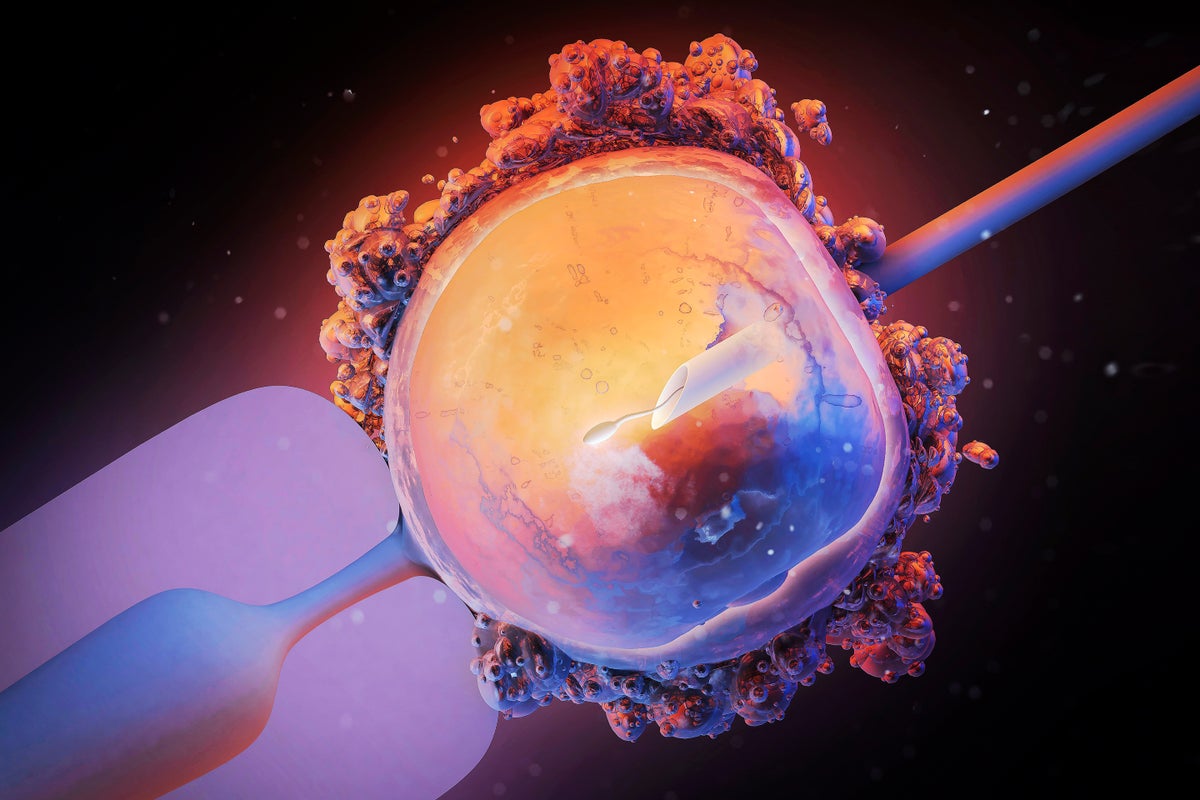

Maurizio De Angelis/Science Source

Eight children in the United Kingdom are living healthy lives — potentially due to a ground-breaking but controversial reproductive procedure aimed at keeping them from inheriting deadly conditions from their mothers, researchers report today.

The infants were conceived through mitochondrial donation, a technique that involves transferring the nucleus of a fertilized egg that has faulty mitochondria — cells’ energy factories — into a donor egg cell with healthy mitochondria. It aims to prevent babies inheriting harmful mutations from their mother’s mitochondrial DNA, which can cause debilitating diseases affecting power-hungry tissues such as those in the heart, brain and muscles.

“This is a landmark study on preventing mitochondrial disease,” says Dietrich Egli, a stem-cell scientist at Columbia University in New York City.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The procedure has been dubbed three-person in vitro fertilization (IVF), because the resulting children carry nuclear DNA from a biological mother and father, alongside mitochondrial DNA from a separate egg donor.

Rare procedure

The UK became the first country in the world to explicitly regulate mitochondrial donation in 2015, after more than a decade of research, discussion and debate. Just one UK clinic, the Newcastle Fertility Centre, has been licensed to carry it out by fertility regulator the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

The latest studies — published in the New England Journal of Medicine — are the first detailed reports of the Newcastle team’s efforts. In 2023, the Guardian newspaper revealed that up to five UK children had been born using mitochondrial donation. But there were few details about the children’s health and other questions surrounding the technique’s effectiveness.

In total, 22 women carrying disease-causing mitochondria went through a mitochondrial donation procedure called pronuclear transfer, leading to eight births (including a pair of twins) and one ongoing pregnancy, report reproductive biologist Mary Herbert, now at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and her team.

The children — four girls and four boys — were all born healthy and are developing normally. The oldest child is now over two years old, the youngest under five months. Five children have had no health problems at all, one experienced muscle jerks that went away on their own, another child was successfully treated for high level of fat in their blood and a heart-rhythm disturbance, a third had fever due to a urinary tract infection.

“We’re cautiously optimistic about these results,” Robert McFarland, a paediatric neurologist at Newcastle University who co-led one of the studies, said at a press briefing. “To see babies born at the end of this is amazing, and to know there’s not going to be mitochondrial disease at the end of that.”

Mitochodrial donations have been performed in several other countries without explicit regulation — mostly as a fertility treatment, but, in at least one case, to prevent mitochondrial disease.

Pathogenic mitochondria

When shuttling the nucleus of a fertilized egg into a donor egg cell that has been emptied of its nuclear DNA, some of the pathogenic mitochondria can be carried along with the nucleus. As the embryo develops, the proportion of pathogenic mitochondria could amplify to levels high enough to cause disease.

Herbert’s team detected no or very low signs of pathogenic mitochondria, carried over from the mothers’ egg, in five children. In the remaining three, the proportion of pathogenic mitochondria varied from 5% to 16% of the total. “This is higher than we would have expected,” Herbert said at the briefing.

These levels probably aren’t high enough to cause disease, says Paula Amato, a reproductive endocrinologist at the Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. But the researchers looked only at cells collected from blood or urine at birth, and levels of mutant mitochondria could be higher in other tissues and organs and change over time, she adds, so the children’s health should be followed closely.

Of the three children with detectable levels of pathogenic mitochondria, two are female and at risk of transmitting these mutations to their own children. Prenatal genetic testing could prevent this, say Egli and others.

Dagan Wells, a reproductive geneticist at the University of Oxford, UK, says his team detected carried-over mitochondria in two out seven children conceived through mitochondrial donation as an infertility treatment in Greece. “It does suggest we have to keep a close eye on this, and it’s not necessarily a guaranteed avoidance of disease transmission,” he says.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on July 16, 2025.

Source link