The Benefits of Raising Conscientious Kids

My preschooler is obsessed with rules—and, more importantly, exploring their loopholes. When I tell him to stop throwing rocks, he will drop a rock dramatically with a loud thud, assuming plausible deniability. He will chase his little sister around our kitchen island, pretending to be a Tyrannosaurus rex, and push her. “Don’t push your sister,” I command, and he will reply, “I didn’t push her! The dinosaur did it.”

Self-control is one’s ability to navigate between multiple competing desires—such as between listening to your mother or shoving your sister. We tend to idolize people who show certain kinds of self-control (like professional athletes) and demonize those we think don’t show enough (like athletes who get caught in doping scandals).

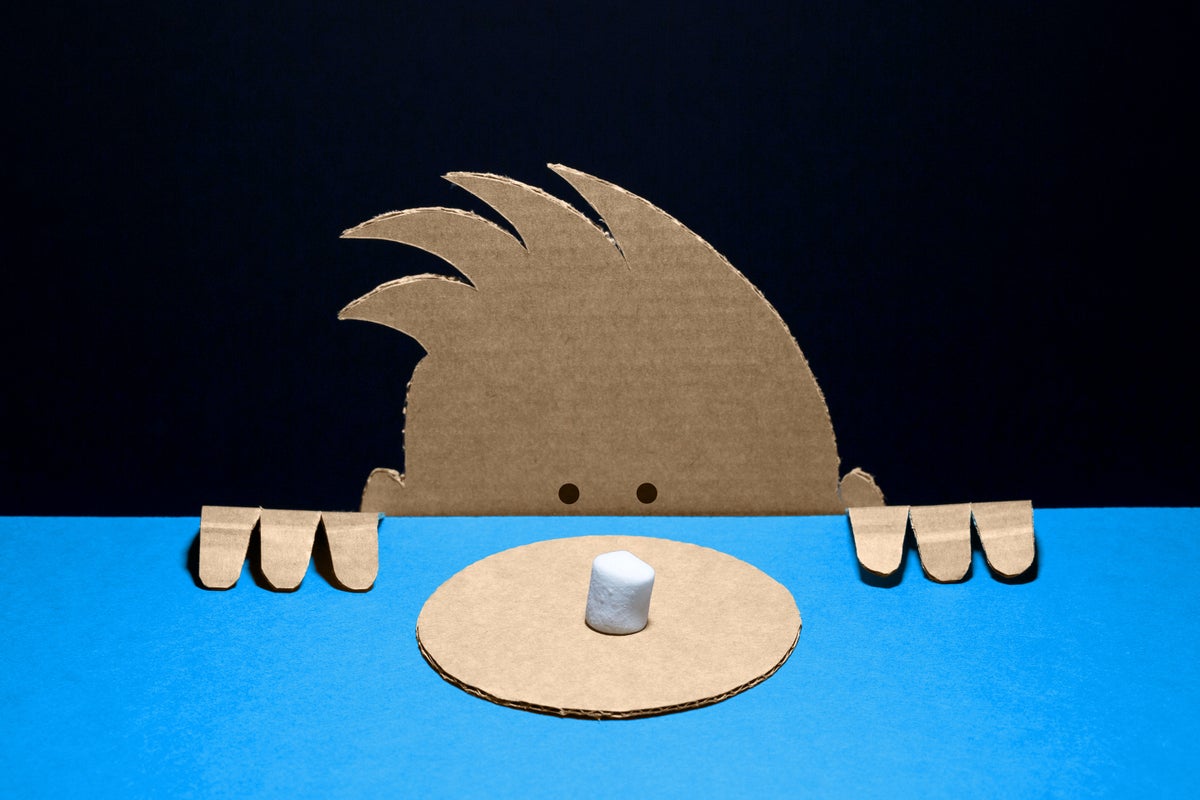

When I think about self-control in children, I think about the famous marshmallow test, where children could either eat a single marshmallow immediately, or, show self-control, refuse that first marshmallow and be rewarded with two marshmallows later. The original studies found that children who waited for that additional marshmallow had more academic success in adolescence compared to those who gave into temptation.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But what if the marshmallow way to think about self-control is wrong? What if it’s not about just avoiding that tempting first marshmallow but the myriad of other things that go along with it: planning for the future, following rules, working hard and trusting that you’ll indeed get that second reward? In other words: being conscientious.

Teaching conscientiousness—a personality trait that’s about more than self-control—may actually be the path for helping our children be the best versions of themselves.

In a recent review, researchers found that changing in-the-moment self-control (e.g., waiting for that second marshmallow one time) does not lead to months- or years-long changes in how consistently we wait for that second marshmallow. Unfortunately, changing our personalities to resist temptation is not so easy. In fact, people who show more consistent self-control don’t necessarily do so all the time. On the contrary, they just avoid temptation in the first place, so that they don’t have to exercise restraint and show less (not more) self-control in their daily lives.

Even the results from the classic marshmallow test are more complicated than first thought. Performance on the test and future academic success are related not just to self-control but to factors like a child’s general cognitive ability or how much education their parent has. Further, it does not seem that one’s ability to wait for that second marshmallow is related to success into adulthood.

Conscientiousness is one of the Big Five personality traits that predict academic success (alongside extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, and neuroticism). Conscientious people tend to show self-control, but they also follow rules, show up on time, and work hard.

Conscientiousness is often underappreciated. One study found that new mothers hoped that their babies grew up to be extraverted and agreeable but consistently ranked conscientiousness as less preferred than almost all other traits. If extraversion is the life of the party, and agreeableness is that one friend who laughs at all of our jokes, we may have a tendency to view conscientiousness as a wet blanket, that person who asks to turn the music down or has to leave early to get to bed on time.

Conscientiousness, however, is associated with the same (and arguably more) benefits that we associate with self-control: Conscientious people have better health, are less likely to be depressed, are wealthier and live longer, compared to people who are less conscientious. When compared to extraversion, conscientiousness is more strongly related to academic success, work performance and lower rates of substance use. Conscientious people have grit.

Rather than the dud at the party, think instead of your friend who always remembers your birthday, that co-worker who volunteers for the hardest assignment, or a judge who upholds the law even when it is unpopular. We could use more conscientiousness in our world.

Conscientiousness appears to be about 40 to 50 percent heritable, so conscientious parents tend to raise conscientious kids. This also suggests that environment and upbringing play a substantial role in whether people become conscientious adults.

Authoritative parenting, characterized by warmth, structure and limit-setting, appears to be related to higher rates of conscientiousness in children. Authoritative parenting is also related to secure attachment between parents and children, which is associated with more conscientiousness.

One way we could practice authoritative parenting and translate some of these ideas into practice could involve explicitly explaining to our children why we make the rules we make. An early sign of conscientiousness may be how readily children follow their parent’s instructions and how positively they embrace family rules. That suggests that parents who expect children to behave in such a manner may help children become more conscientious over time. Rather than simply telling my son he shouldn’t shove people “because I said so,” I could explain that our family believes it’s important not to hurt others and that we don’t push others because we could hurt them (even when you’re a dinosaur).

We can also look at what conscientious people do in their daily lives outside of self-control behaviors and try to model those other actions for our kids. If we want to model punctuality and responsibility, we could explain why it’s important for our family to show up for a playdate on time and then (heroically!) do it. We could also describe to our kids all the things we need to do—pack snacks, put gas in the car, feed the dog—before we can get to our friend’s house as a way to model good planning.

Thinking about the research on how adults who show more consistent self-control often exhibit less, not more, self-control moment-to-moment, we might try to provide our children with opportunities to safely test boundaries and allow their impulses some freedom. Sometimes our family has what we call “yes days” where we try to say “yes” to whatever our kids desire (within reason) for an afternoon. Milkshakes for dinner? Sure. Go chase some birds at a park for hours? Go wild.

Cultivating conscientiousness in our children may not only help them thrive but help us manage our own stress. One study found that traits like agreeableness and conscientiousness in French children were related to less burnout in their parents, including parents reporting less emotional exhaustion and more self-efficacy in their parenting.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about how conscientiousness develops. Personality traits are hard to change, as are cognitive skills depending on your child’s abilities. For example, if your child has ADHD or is otherwise neurodiverse, a change in parenting practices alone is likely not enough to help that child become more planful or rule-abiding. It might take longer. Conscientiousness might look different than in other kids. All children, regardless of ability, deserve parents with realistic and flexible expectations around the potential for change as we work towards nurturing conscientiousness in our families.

It’s tiring to explain to my son for the hundredth time why we don’t shove people. The other day, however, my daughter decided to shove her brother, and I heard him explain to her in a tone not unlike my own, “We don’t push people in our family!” As he came running to tattle on his sister, all I could do was laugh.

Source link