Addiction Risk Shows up in Children’s Brain Scans before Drug Use Starts

Massive Study Flips Our Story of Addiction and the Brain

Brain differences in children and teens who experiment with drugs early show up before they take their first puff or sip

Mehau Kulyk/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

For decades, Americans have been told a simple story about addiction: taking drugs damages the brain—and the earlier in life children start using substances, the more likely they are to progress through a “gateway” from milder ones such as marijuana to more dangerous drugs such as opioids. Indeed, those who start using at younger ages are much more likely to become addicted.

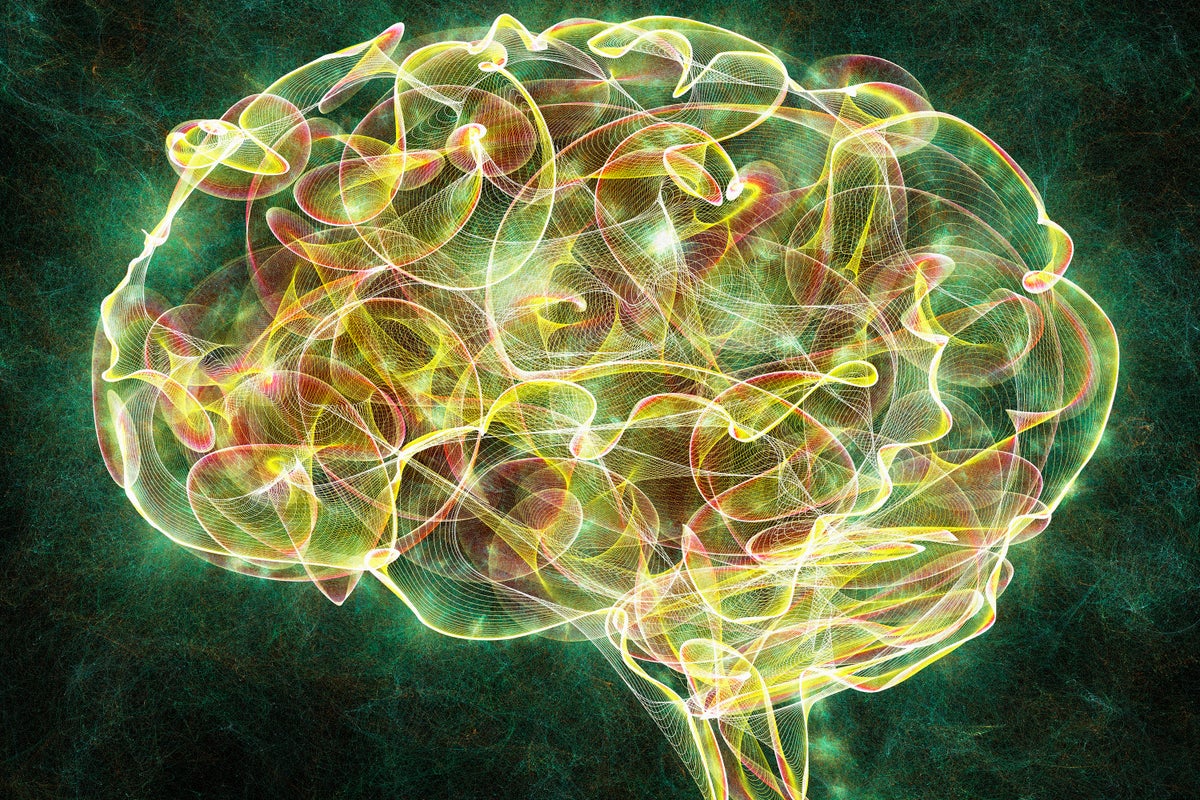

But a recent study, part of an ongoing project to scan the brains of 10,000 kids as they move through childhood into adulthood, complicates the picture. It found that the brains of those who started experimenting with cannabis, cigarettes or alcohol before age 15 showed differences from those who did not—before the individuals took their first puff or sip. When paired with an independent trial of a successful prevention program tailored to at-risk kids, the findings suggest better ways to fend off substance use disorders before they start.

“This study is extremely helpful because it begins to outline the brain changes that are seen in teenagers who start to use drugs early,” says Ayana Jordan, an associate professor of psychiatry and population health at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, who was not associated with the project.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The findings are “actually telling you that there are vulnerability factors and identifying them,” says Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health, which funded the research. Published in December 2024 in JAMA Network Open, the new work is part of the ongoing NIDA-led Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development initiative, the largest-ever long-term U.S. study of child brain health and growth. (Like all current NIH projects, it is threatened by the budget cuts imposed by the Trump administration, though Volkow says sustaining it is a top priority for NIDA.) In the new study, children aged nine to 11 underwent regular brain scans for three years. In separate interviews, the participants and their parents also provided information on diet and substance use. Nearly a quarter of the children had used drugs including alcohol, cannabis and nicotine before the study began.

Children who started using drugs during the study period had preexisting enlargements in many brain regions and had larger brains overall when the study began than those who did not use drugs, explains lead author Alex Miller, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Indiana University School of Medicine. These youth had many of the same brain differences as children who had begun drug use before the start of the study. In both groups, the outer portion of the brain, called the cortex, also had a larger surface area on average, with more folds and grooves.

Having a bulkier and more heavily creased brain is generally linked to higher intelligence, though these factors are far from the only ones that matter. Bigger and groovier isn’t always better: during adolescence, natural processes actually “prune back” some brain areas—so whether size differences are positive depends on the life stage being studied and on the brain regions that should be large at that time.

Other research has associated the some of the brain differences found in the study with certain personality traits: curiosity, or interest in exploring the environment, and a penchant for risk-taking.

Like having a large brain, curiosity and interest in novelty (which are sometimes measured together as a personality trait called “openness to experience”) are associated with intelligence. But when curiosity is coupled with a strong drive to seek intense sensations and a willingness to take risks without considering the consequences, it’s also linked to a higher likelihood of trying drugs.

If these early brain differences aren’t caused by drugs, where do they come from? They could reflect certain genetic variations or childhood exposure to adverse experiences—both of which have previously been associated with addiction risk. While it’s still possible that substances could chemically interfere with brain development, contributing to the elevated risk for addiction among those who start drinking or taking other drugs early, the study suggests that there are other, preexisting factors at play.

The brain differences here were only linked to early initiation of drug use—not necessarily to addiction itself. “More data is needed to see if any of these brain changes are related to disease progression, severity of use or how the teens may respond to treatment,” Jordan says.

Research already suggests that early differences can be targeted to improve prevention programs. In fact, a recent trial showed that substance use disorders can be prevented in kids with personality traits that put them at higher risk. Some of the personality traits targeted in this trial have previously been associated with the kinds of brain differences found in the new brain scan study.

In the prevention trial, researchers compared Montreal-area schools in which teens received a personality-based intervention in seventh grade with those that did not. The program began by having kids take a validated personality test. Months later, with no reference to the test, teens who scored highest in the traits of impulsiveness, sensation-seeking, hopelessness or sensitivity to anxiety were invited to participate in two 90-minute workshops. These workshops taught cognitive skills aimed at maximizing the strengths and minimizing the weaknesses typically associated with their specific most strongly outlying trait.

Five years later, students at the schools that did use the program had 87 percent lower odds of developing substance use disorders. “It’s a 35 percent reduction in the annual growth of substance use disorders across time,” says Patricia Conrod, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Montreal and lead author of the prevention trial. The results were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in January.

Conrod emphasizes that “risky” traits have pluses as well as minuses. For example, a tendency to seek new experiences can be critical for success in science, medicine and the arts. A willingness to take risks is useful in occupations ranging from firefighting to entrepreneurship. The trick is to help young people manage such predilections safely.

In some children she has worked with, who start drugs as early as age 13, Conrod says that “the drive to self-medicate is so strong; it’s really striking. There really is this discomfort with their inner world.” As a result, providing ways to manage these feelings without misusing drugs—and without pathologizing those with outlying traits—can be a powerful way to support healthy development.

Source link