Ancient wasp preserved in amber may have used its rear end to trap flies

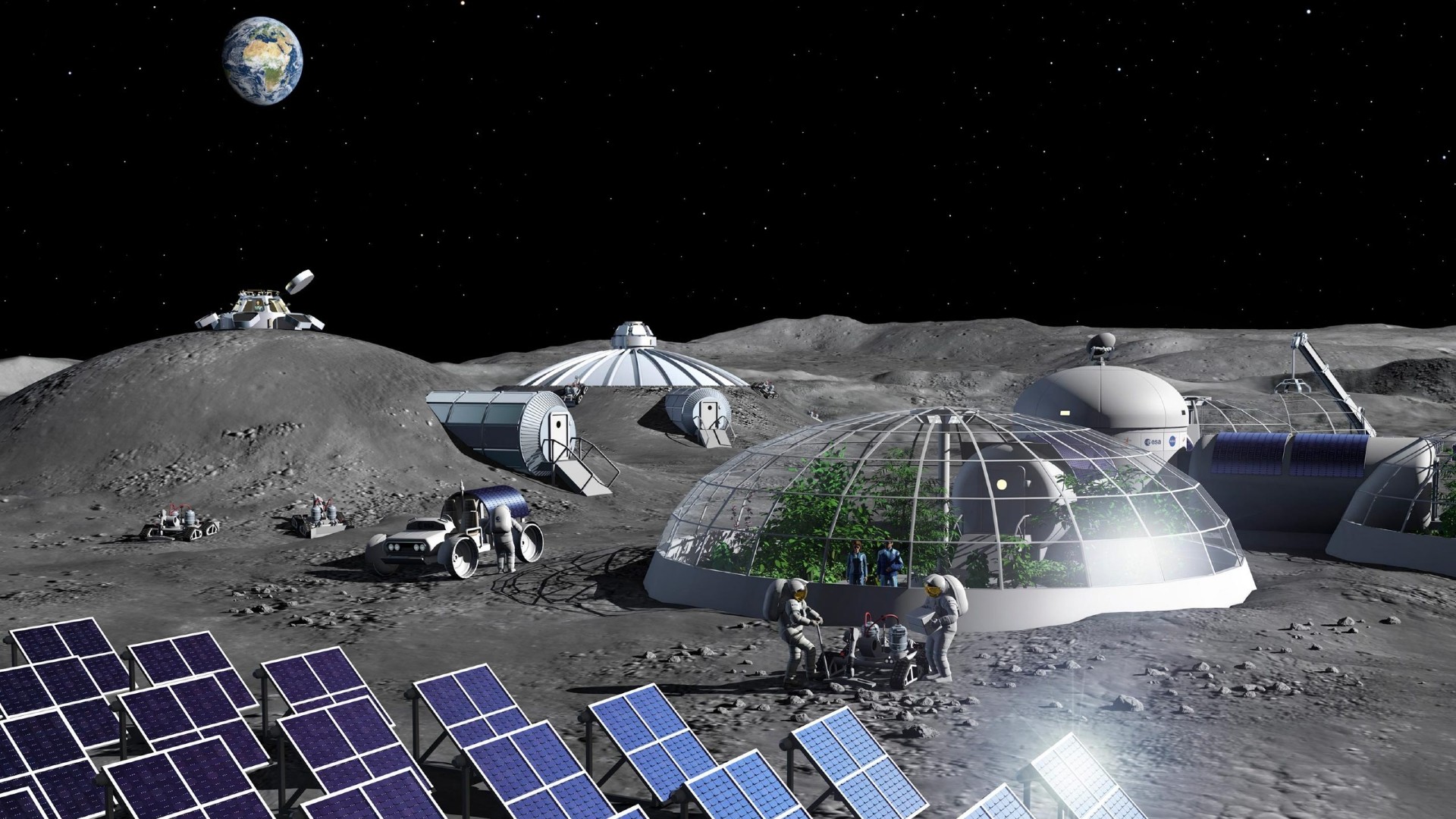

A specimen of Sirenobethylus charybdis preserved in amber

Qiong Wu

An extraordinary extinct wasp found preserved in amber may have used its abdomen to grasp other insects like a Venus flytrap before laying its eggs on them.

“It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen before. It’s unlike any wasp or any other insect that is known today,” says Lars Vilhelmsen at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

Vilhelmsen and his colleagues have named the wasp Sirenobethylus charybdis after Charybdis, a sea monster in Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey. The insect lived almost 99 million years ago in the Cretaceous period.

The researchers used micro-CT scanning, an X-ray imaging technique, to examine 16 female wasps that were encased in amber found in the Kachin region of Myanmar.

All the wasps had three flaps in their abdomens, making up a clasping structure. It was preserved in different positions, sometimes open and sometimes partly closed, suggesting it was a movable, grasping device when the insects were alive.

“It was very exciting, but it was also a challenge, because how can you explain how this animal worked when you have nothing like it today?” says Vilhelmsen.

So he and his colleagues took examples of living and extinct wasps and analysed their characteristics. This revealed that the closest analogues of the wasps in amber were modern-day parasitoid species of the superfamily Chrysidoidea. These include cuckoo wasps, the larvae of which live on hosts as parasites, eventually killing them as they consume them.

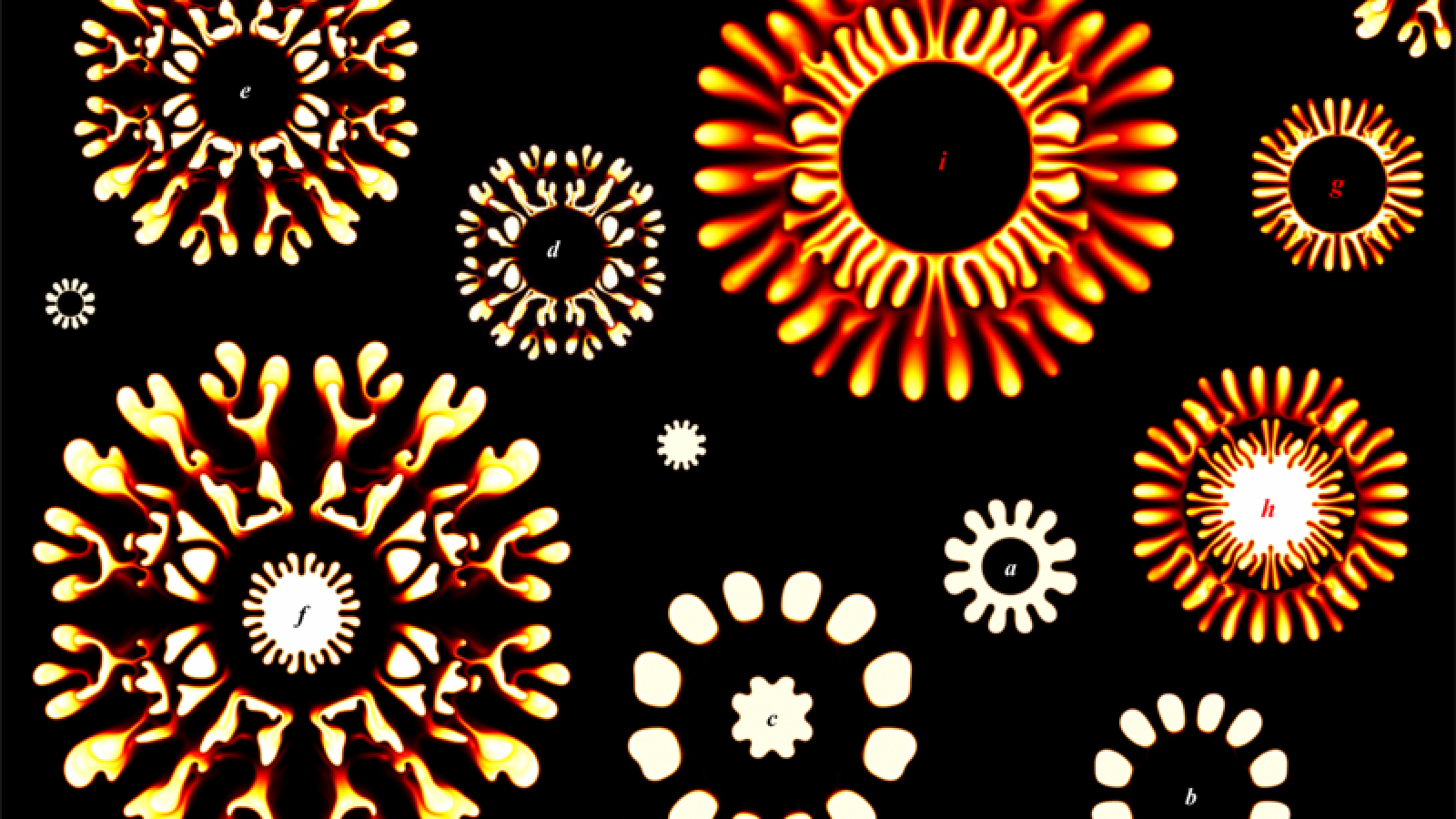

The grasping structure made up of three flaps on the wasp’s abdomen

Qiong Wu

The key to the behaviour of S. charybdis may be the lower flap of the trap-like abdomen, which may have acted like a Venus flytrap plant, says Vilhelmsen. “There are these fan-like elongate trigger hairs, probably sensory hairs, extending from this lower flap. If this had been resting on the surface and the host was walking past, then it would touch these hairs and then maybe the wasp would quickly launch backwards because there was a potential host within reach.”

He suggests that S. charybdis would have waited in ambush for potential victims like flying insects or jumping nymphs with its trap open and then snapped it shut to restrain the host and lay its eggs.

“This is a truly unique discovery,” says Manuel Brazidec at the University of Rennes in France. “What I find extraordinary is that the abdomen of Sirenobethylus charybdis is a brand new solution to a problem that all parasitoid insects have: how do you get your host to stop moving while you lay your eggs on or in it?”

Topics:

Source link