12 pivotal moments in the history of robotics, from Isaac Asimov to self-driving cars

Few technologies have captured the human imagination in quite the same way as robots. The idea of machines that can walk and talk like us has been a staple of science fiction for decades. The reality has been more prosaic — most real-world robots are disembodied arms relegated to dull and repetitive factory work. But recent breakthroughs in both artificial intelligence (AI) and robotic hardware mean that the smart, humanoids of our imaginations are getting ever closer to reality.

Here are 12 of the most important milestones that got us here.

1921 — Invention of the term “robot”

Since antiquity, people had imagined the possibility of artificial humans — from the clay Golems of Jewish folklore to the mechanical servants of the Greek god Hephaestus. History is also littered with examples of complex automata designed to wow audiences with their life-like movements. But the word “robot” was first introduced by the Czech writer Karel Čapek in his 1921 play R.U.R., which stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots). The term is derived from the Czech word “robota,” which means forced labor, and the play features artificial workers made of synthetic organic matter that rise up against their human masters — — a narrative that would be echoed in many later works.

1942 — Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics

Robots became a popular science fiction trope, with legendary author Isaac Asimov featuring them prominently in many of his stories. A major theme of his work was how these artificial humans would interact with human society. In his 1942 short story “Runaround” he introduced the Three Laws of Robotics, which were supposed to govern how all robots in his fictional universe operated. The first law prohibited the robots from harming humans, the second mandated robots to obey humans unless it violated the first law, and the third ordered the machines to protect themselves as long as that didn’t conflict with the two other laws. While entirely fictional, Asimov’s three laws were influential on the development of ethical frameworks for AI and robotics.

1961 — The first industrial robot

It didn’t take long for ideas from science fiction to filter through to the real world. In the early 1950s, serial inventor George Devol began work on a robotic arm that could perform repetitive tasks in factories. He teamed up with entrepreneur Joseph Engelberger to form Unimation, the world’s first robotics company, and in 1961 their Unimate robot went to work on the assembly line at a General Motors plant in New Jersey. The hydraulically-powered arm had five degrees of freedom (DoF) —a measure of dexterity that means its arm could move or rotate in five different directions. Programming the device required the user to physically move the arm to different positions to teach it the required sequence of actions, which was then recorded in a magnetic storage device known as a drum memory.

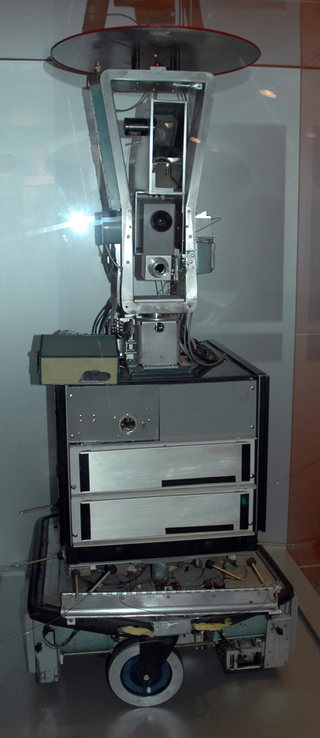

1966 — World’s first intelligent mobile robot

While significant progress had been made on the mechanical capabilities of robots by the mid-1960s, they were still essentially dumb machines that needed to be programmed by hand. In 1966, researchers at the Stanford Research Institute started work on a wheeled robot with cameras and touch sensors that could reason about its actions, make plans and navigate the real world. It could move between multiple rooms autonomously, avoiding obstacles, opening doors, flicking light switches and pushing boxes around. The robot, which the team named “Shakey,” received significant media attention— in 1970 — Life magazine even referred to it as the first electronic person.”. A key advance behind the robot was its layered software architecture, which enabled it to reason through tasks, something replicated in many subsequent robots.

1969 — The Stanford Arm spawns a new industry

While the Unimate was the first robotic arm to go into production, the Stanford Arm became the blueprint for the emerging industrial robotics industry. Designed in 1969 by Victor Scheinman, who was then a student in the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab, the six-DoF arm was electrically powered and controlled by a computer. Over the following years Scheinman built increasingly sophisticated versions of the arm at both Stanford and MIT, before eventually starting a company called Vicarm Inc. in 1974 to commercialize his work. He ended up selling his designs to Unimation in 1977, which released the Programmable Universal Machine for Assembly (PUMA) robot in 1978. The initial customer was General Motors, which used it to assemble automotive subcomponents.

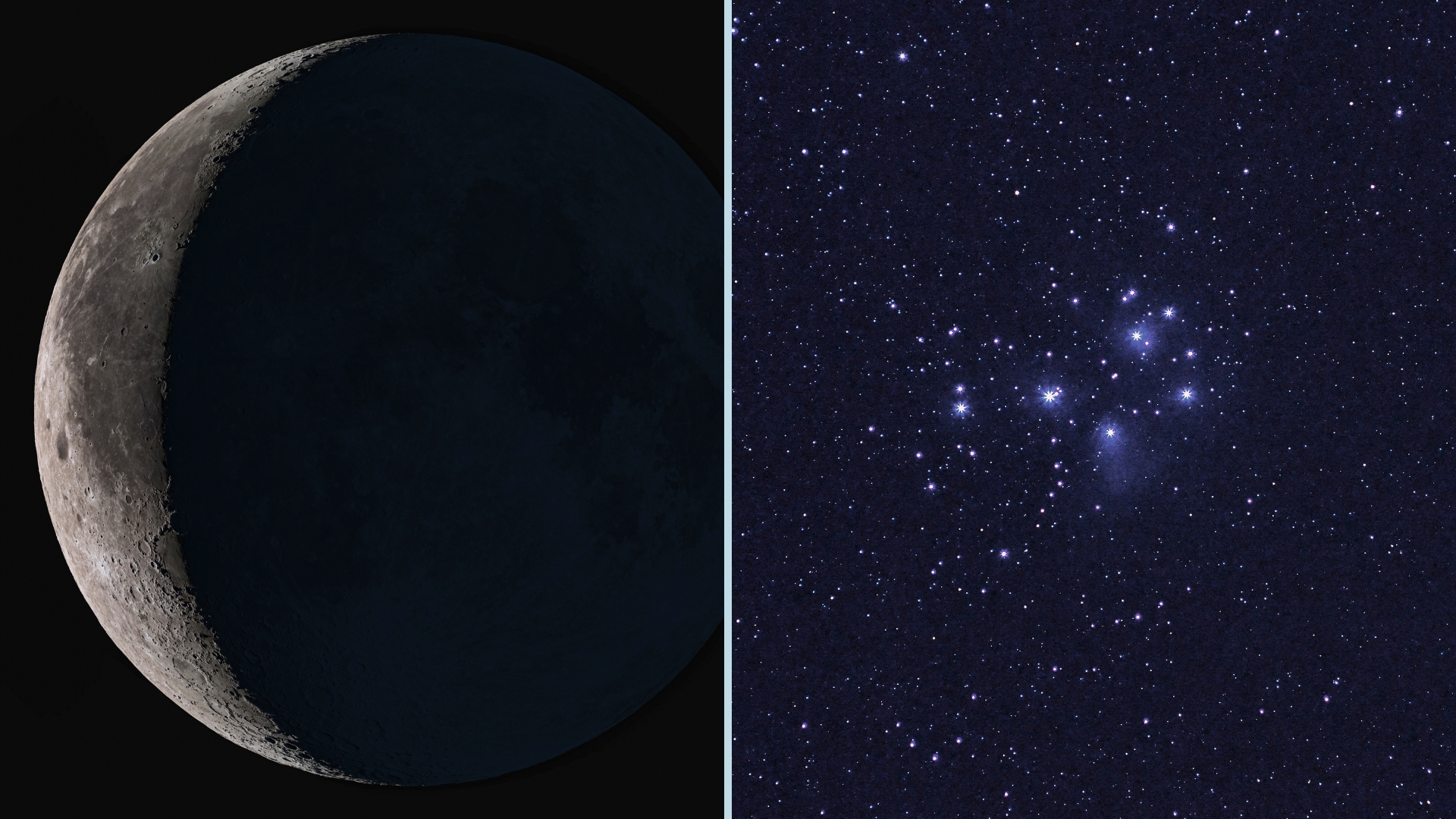

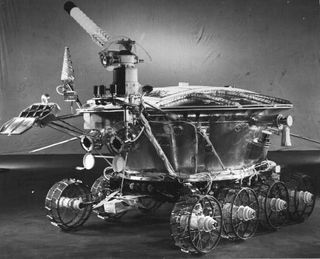

1970 — First robotic rover sent to the Moon

The birth of robotics overlapped with another major technological leap— — the advent of the Space Age. Scientists recognized that machines that could be controlled remotely or even operate autonomously could be a powerful tool for exploring the solar system. In 1970, the Soviet Union landed Lunokhod 1, the world’s first robotic rover, on the moon. Shaped like a bathtub and with eight independently powered wheels, the rover could be controlled remotely from Earth via antennas and a feed from four cameras. The solar-powered vehicle operated for almost a year, roughly three and half times longer than it was designed to last, and travelled 6.5 miles (10.5 kilometers). It also used extendable probes to carry out more than 500 tests on the mechanical properties of lunar soil.

1990 — Rodney Brooks rewrites AI for robotics

By the 1980s, industrial robots that could carry out repetitive tasks in controlled environments had become commonplace, but efforts to create more flexible and autonomous machines were foundering. Australian roboticist Rodney Brooks had the intuition that this plateau was due to the top-down approach researchers were taking. This involved a focus on imbuing machines with abstract reasoning skills and developing complex systems of mathematical symbols to represent the world around them. Instead, he took inspiration from nature and focused on the feedback loops between sensing and action that enable sophisticated behavior in animals. He demonstrated that by taking this bottom-up approach, outlined in the 1990 paper Elephants Don’t Play Chess, it was possible to combine multiple simple behavioral modules to solve challenges beyond the robots that existed at the time.

1996 — Honda unveils first humanoid walking robot

Despite considerable progress in robotics, most machines were a far cry from the mechanical people depicted in sci-fi. That changed in 1996 when Honda unveiled its P2 robot, which was the first humanoid robot capable of walking independently on two legs. The company had started working on the problem of bipedal locomotion in the late 1980s by studying, and trying to replicate, how humans walked. Research on P2 and its successors P3 and P4 eventually culminated in the development of the company’s iconic ASIMO humanoid robot, which was unveiled for the first time in 2000 and set the standard for humanoid robotics going forward.

2000 — The da Vinci surgical robot cleared by the FDA

While most commercial robotics companies focused on machines designed to replace brute labor in factories, Intuitive Surgical decided to focus on the delicate process of minimally invasive surgery. They built a four-armed robotic surgical system called da Vinci that could be controlled remotely by a surgeon. The arms were capable of holding surgical instruments like scalpels, graspers and scissors and enabled the surgeon to carry out ultra-precise movements. The device was cleared for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2000 and has been used in more than 14 million procedures.

2010 — Google unveils self driving car project

There had been scattered experiments in autonomous vehicles over the years, but the first company to devote serious resources to the idea was Google. The firm began developing self-driving cars in 2009 and drove more than 140,000 miles on public roads before announcing the project in October 2010. Earlier experiments were carried out in a modified Toyota Prius with a safety driver behind the wheel. But in 2015 the company carried out the first fully autonomous ride on a public road in a custom-built vehicle with steering wheel or pedals. After rebranding as Waymo, the company started its first public trials of a driverless taxi service in Phoenix, Arizona in 2017. TK should we mention you can now pay for these rides here in San Francisco? They drive down my block ALL the time.

2012 — The DARPA robotics challenge is launched

One of the major catalysts for recent breakthroughs in smart, humanoid robots was the DARPA Robotics Challenge. Launched by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in 2012, the competition challenged teams to develop semi-autonomous robots that could carry out complex tasks in simulated disaster zones. The bots were tasked with walking across rubble, climbing ladders, closing leaky valves and even driving a utility vehicle. The finals were held in 2015. While some teams competed with their own robots, six were provided with humanoid Atlas robots built by Boston Dynamics. The company continued to develop the robot after the competition was over, showing off increasingly advanced capabilities over the years such as running outdoors, jumping and tackling parkour courses.

2020 — The first bipedal robot goes on sale

Watch On

The startup Agility Robotics became the first company to release a commercial bipedal robot after selling two units of its Digit model to Ford. While not strictly a humanoid, thanks to its “backward” legs that work more like a bird’s than a person’s, the robot is roughly the size and shape of a small human and designed to help out in warehouses and other industrial settings. The release marked the beginning of a boom in commercial humanoid robotics, with companies like Tesla, Figure and 1X unveiling their own offerings shortly afterwards. And costs are falling rapidly — earlier this year Chinese company Unitree released its G1 humanoid robot, which costs just $16,000.

Source link